Rochester has spent the past year honoring abolitionist, orator, and publisher Frederick Douglass, who spent a substantial part of his life here. As part of that observance, Open Mic Rochester and CITY have focused on Douglass’s life and work and asked how well Rochester has lived up to his legacy.

In the last of that series, the focus is a subject in which Douglass had an intense personal interest: education. Douglass learned to read as a child in slavery, taught first by Sophia Auld, the wife of slave owner Hugh Auld. And when she stopped the lessons on her husband’s orders, Douglass found other people to help him learn – and learned on his own. He knew that slave owners were afraid of the power of education, and he knew the potential education held for him.

As an adult, Douglass credited education for his freedom – physical and mental. “Some men know the value of education by having it,” he said. “I know its value by not having it.”

In Rochester, Douglass fought for an equal education for his daughter and lashed out editorially in The North Star at adults who wanted to segregate black students from whites. And on his national tours, he spoke frequently about education, its importance in his own life and the impact its denial had on slaves.

For his address at the dedication of a school for black children in Manassas, Virginia, Douglass wrote a speech he titled “Blessings of Liberty and Education.” In it, he noted the significance of the school: “To found an educational institution for any people is worthy of note,” he said, “but to found a school in which to instruct, improve and develop all that is noblest and best in the souls of a deeply wronged and long neglected people, is especially noteworthy.”

And he bore down on the importance of education. A human being, Douglass said, “is only potentially great. As a mere physical being, he does not take high rank, even among the beasts of the field. He is not so fleet as a horse or a hound, or so strong as an ox or a mule. His true dignity is not to be sought in his arm, or in his legs, but in his head. Here is the seat and source of all that is of especially great or practical importance in him.”

“There is fire in the flint and steel,” Douglass said, “but it is friction that causes it to flash, flame and burn, and give light where all else may be darkness. There is music in the violin, but the touch of the master is needed to fill the air and the soul with the concord of sweet sounds. There is power in the human mind, but education is needed for its development.”

“To deny education to any people,” Douglass said, “is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness, and to defeat the very end of their being.”

The Open Mic-CITY series on Frederick Douglass wraps up at a crucial time for education in Rochester. The Rochester school district is under intense fire. Despite decades of well-intentioned efforts, the district’s student achievement level is one of the worst in the state. The school board – which is beginning the search for yet another new superintendent – is severely divided and fractious. And state and local officials are questioning whether the district, as it’s constituted now, can fix itself.

What would Douglass think now of the state of education in the city he loved? In this final segment, seven Rochesterians – community leaders, students, and parents – offer their assessment and their advice.

‘Rochester sits squarely in the middle of a national challenge’

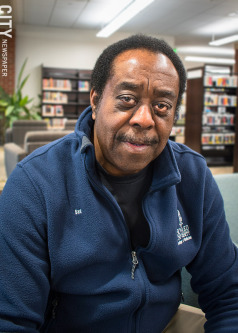

BY BEN DOUGLAS

PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s brilliant play, “Hamilton,” inspired by Ron Chernow’s detailed biography of Alexander Hamilton, and David W. Blight’s exhaustive biography of Frederick Douglas have brought into vivid focus two giants of American history. These two figures, although very different, had some striking things in common. Both were poor, of illegitimate birth, possessed a passionate desire to succeed, and had their path to their future opened through education.

Hamilton traveled from his childhood home in the Caribbean to New York with the support of others at about the age of 17 to pursue his formal education.

Douglass, on the other hand, had quite a different path to self-education. His intellectual passion was lit inadvertently by his owner’s wife, Sophia Auld. She had begun to teach the young Douglass his ABC’s, had given him rudimentary spelling lessons, and read to him regularly from the Bible. When their activity was discovered by Sophia’s husband, Hugh Auld, he sternly ordered the lessons to stop, declaring that slave literacy was “unlawful” and that “learning would spoil the best n—-r in the world.”

The impact on Douglass was profound. In his words, Auld’s verbal abuse was “the first antislavery lecture to which it had been my lot to listen.” Author David Blight wondered about Sofia Auld: “Could Sophia even have grasped the power she had unleashed in Frederick?”

“The more I read,” Douglass wrote, “the more I was led to abhor and detest slavery, and my enslavers” – “As I read, behold! The very discontent so graphically predicted by Master Hugh had already come upon me… the revelation haunted me, stung me and made me gloomy and miserable.”

Douglass went on to become a powerful orator, abolitionist, author, and newspaper publisher, and had huge influence nationally and internationally. His speeches drew heavily upon the logic and morality of the Bible. Among other achievements, he was an ambassador to Haiti and Marshall of the District of Columbia.

From the end of slavery forward, there are many stories of individuals whose intellectual pursuits allowed them to loom large on the national stage and in the pages of history through the educational support of historically black colleges. One such college, Howard University, which is mentioned prominently in Blight’s book, can claim among its many notable graduates Kamala Harris, US Senator and candidate for president, and Emmet Sullivan, judge of the US District Court for the District of Columbia.

Sullivan is the jurist who demanded that a child removed from her father at the southern border by the Justice Department, who had been clandestinely flown to her home country against his orders and without her father, be returned or he would hold Jeff Sessions, the US Attorney General, in contempt. The child was hastily returned.

Sullivan is also the judge who will determine the sentence of convicted former National Security Advisor General Michael Flynn.

In the past, the struggle was to provide education to those who were long denied it, and then to do so with poorly funded and substandard schools. Today the challenge is to educate urban communities struggling with concentrated poverty with all the barriers that entails.

Unfortunately, Rochester sits squarely in the middle of this challenge as a city that ranks high on the list of communities with severe concentrated poverty. Fortunately, the energy and concern to tackle these problems are continuing. I salute those who work hard each day in education and encourage those on the sidelines to become engaged. Rochester’s children, indeed, Rochester’s future requires us to do so.

Still, the central question remains; how are Rochester’s schools doing?

The Rochester Business Journal’s 2018 “Schools Report Card” for Monroe and Ontario Counties offers a place to start. For the 2016-2017 school year, Rochester ranked at the very bottom in percentage of Regent diplomas and performance on regent English, math, and SAT exams. In assessing individual high schools in the same categories, Rochester had a few higher-ranking schools, but most settled out near the bottom. The eight and fourth grade exam results and individual school rankings were dismal.

That the students who attend these poorly performing schools come from poor neighborhoods is inescapable. That most of these students are racial minorities points to the impact racism and socio-economics have on urban education.

Is it possible to adequately educate poor urban kids with language, social, family, and other life challenges? Starting with the 2014-2015 school year, East High School, a low-performing school threatened with state-forced closure, partnered with the University of Rochester to approach urban education differently. The collaborators made changes that could not be done easily within the Rochester School District. The improvements so far have been substantial and encouraging.

So what is different? It seems the East approach focuses on putting the students’ needs at the center of everything the school does, including an administration that is high on accountability and cohesive educational planning through all grade levels. It provides services that support their student’s ability to stay in school and engage students and supportive volunteers in the entire process. They hire their own teachers and annually assess which teachers should stay and which should move on.

Isn’t this what the Rochester School district does? According to Jaime Aquino, a consultant sent by state Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia to assess our schools’ poor performance, it does not. Another central question remains, then: If this kind of educational support is not happening, why not?

Ben Douglas is a former member of the Rochester City Council and the Rochester School Board and is the parent of two adult children

‘We’re still getting the short end of the stick’

BY BRIA ADAMS

PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

During Black History Month, we reminisce about past and present iconic figures in the black community. Although Rochester now symbolizes garbage plates and lilac flowers, we once symbolized a light at the end of the tunnel for enslaved people from the South.

One honorable abolitionist who assisted Rochester to be the city we are today is Frederick Douglass. The Flower City was Douglass’s home for much of his life. Here he published newspapers, reinforced women’s voting rights, and took in runaway slaves following the Underground Railroad.

Having learned how to read as a young person, Douglass clearly understood that education was essential. He lived up to his own words, “Once you learn to read, you will forever be free,” by continuously reading and writing to mentally escape as a slave.

Although the physical form of slavery has been abolished in the United States, mental enslavement has been long lasting for all races. As a Rochester school district student, I believe that even my own school is mentally enslaved by poverty related to racial stereotypes and segregation. Now I ask myself: Is our education system living up to Douglass’s dream? The answer is a stern “No.”

Frederick Douglass prioritized not just equality but integration as well. He wanted everyone to have the rights of an American. Within our city schools today, the population of students is mostly black while the population of suburban schools is mostly white. Slavery was abolished more than a century ago, yet we’re still divided.

Douglass would want us to get the same education despite our skin color, our home location, and our interest in learning. We’ve identified the issues of segregation and education inequality, but we must find the steps to heal our education system and expand the minds of the belittled.

To improve our school systems, we must start by valuing each student the same. We have to treat every learner the same despite talent, interest, disability, race, sexual orientation, and so on because that is what Douglass would want. Many times we take the education we get and settle for less. We’re afraid to ask for the same education as the white child. The abolitionist would not want us to be afraid to ask for a better education, because as a people we were once denied an education.

Today in Rochester, the education system and school districts are doing the opposite of what Douglass fought for. We are divided and are still getting the shorter end of the stick.

Bria Adams is a senior at East High School.

‘We can’t ignore poverty and segregation’

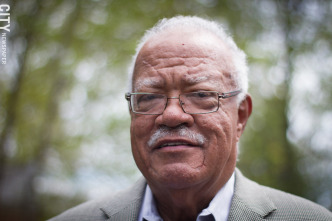

BY MALIK EVANS

Monroe County.” PHOTO BY RENÉE HEININGER

Frederick Douglass once said that “without struggle there is no progress.” I am often asked that, as the city of Douglass, why in the 21st century are the disparities so stark in the areas of race, income, housing, and educational quality in Rochester? I often answer with that we have come a long way from where we were, but we still have a long way to go.

This could not be more apparent than in the field of education. Rochester continues to struggle in every major category and ranks last in the state in on-time graduation rates. The concentration of poverty affecting largely African American students falls disproportionately to city schools.

Seeing this challenge as just a city problem is dangerous. This is a regional and state issue. A state of emergency should have been called 30 years ago. We have spent years nibbling around the edges instead of calling for a complete overhaul of the entire school system.

Rochester and the state of New York bill themselves as a “progressive” place to live. This hides the dastardly de facto segregation that exists in our education system.

New York schools rank as the most segregated in the country, according to a report titled “New York State’s Extreme School Segregation: Inequality, Inaction, and a Damaged Future.” This report, by UCLA author and researcher John Kucsera, should be required reading for anyone who cares about equality and justice. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education declared that separate schools were inherently unequal. Sadly, almost 65 years later Rochester’s schools are more segregated than ever.

Rochester has a great pre-kindergarten program and has modernized many of its schools through the Facilities Modernization Program. However, this has not erased the concentration of poverty and the extreme segregation that exists in our schools in Monroe County. This has contributed to the achievement gap.

There are models in the country that we should be adopting in Monroe County. We need only look to Raleigh, North Carolina, a state where segregation existed for many years but now has some of the most diverse schools in the country. Not only are the schools diverse, they are also high performing.

The goal in schools in Raleigh is to limit low-income students in each school to 40 to 50 percent of the student body. This should be a requirement in every school in Monroe County and the state. If this requires dissolving boundaries and reconstituting jurisdictions, so be it. We are now past the time of being able to live as if we were living on islands while inequity continues to be right at our shores.

The organization Great Schools for All has highlighted the Raleigh model for years. Let me be clear: Frederick Douglass has taught us that poverty and segregation are not excuses, but they are factors that we cannot ignore.

Douglass reminded us that we ignore these factors at our own peril, especially as it relates to education when he stated: “Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.” My hope is that as a community we can live up to the life and work of Frederick Douglass, by ensuring that education is an equalizer for all of Rochester’s children.

Malik Evans is a member of the Rochester City Council, is former president of the Rochester school board, and is the parent of two children.

‘Many public schools don’t prepare the human intellect or heart for education’

BY CYNTHIA ELLIOTT

graduate are prepared for a global economy.”

PHOTO BY RENÉE HEININGER

I count Frederick Douglass as one of the greatest men who ever lived. It wasn’t until I read some of his writings and specifically his speech, “What to the Slave is the 4th of July” – given in Rochester, by the way – that I truly appreciated his bravery. He was able to educate himself such that his education propelled him to become one of the greatest abolitionist in history.

How has Rochester has lived up to his legacy and aspiration in education? We have not. Too few African American students who graduate are prepared for a global economy. Moreover, too few African American students are prepared to effectively handle the increase in racism in our schools and in our nation.

While some African American families have made the choice to place their children in charter schools, which have mixed results, there is now a trend among African American families towards home schooling. In the article “The Rise of Homeschooling Among Black Families,” Jessica Huseman writes, “African American parents are increasingly taking their kids’ education into their own hands – and in many cases, it’s to protect them from institutional racism and stereotyping.”

Further, Huseman writes, “Studies indicate that black families are more likely to cite the culture of low expectations for African American students or dissatisfaction with how their children – especially boys – are treated in schools.” The same article criticizes public schools, noting that black students are being robbed of the opportunity to learn about African and African American culture. With regard to the African American history curriculum, parents have noted that in traditional public schools it begins with slavery and ends with the Civil Rights movement.

Douglass knew that education is vital to human growth. Education transcended him from a slave to a free man. In his book “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” he writes, “slavery was a poor school for the human intellect and heart….”

Many public schools are like slavery in that they do not prepare the human intellect or the heart for education. For black students, education is the key to moving out of poverty and to the road of self-sufficiency. Home schooling seems to be the educational alternative these parents are considering to ensure their children are prepared for life.

Consider the numbers: In the last 15 years, black home schooling has doubled from 103,000, to 220,000. Douglass understood the power of education. Parents understand the power of education. I think Douglass would be inspired to know that parents are using whatever mean necessary to educate their children. Homeschooling, for African American parents, seems to be one of those alternatives.

Cynthia Elliott is vice president of the Rochester School Board and is assistant to the executive director of Baden Street Settlement.

‘Students need a variety of options’

BY TANIYA GAINES

and motivation.” PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

Years after Frederick Douglass escaped slavery, he called Rochester his home for 25 years. His story of how he taught himself to read and write shows us how important a quality education is. Once he learned to read and write, his life forever changed, and he realized that his only way to freedom was to have an education.

Douglass writes: “Without education he lives within the narrow, dark and grimy walls of ignorance. Education, on the other hand, means emancipation. It means light and liberty. It means the uplifting of the soul of man into the glorious light of truth, the light by which men can only be made free. To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is easy to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness and to defeat the very end of their being.”

Douglass is highlighting the importance of education as part of the process of reaching freedom. Every child should have the right to receive a quality education so that they are able to gain the skills and knowledge needed to overcome future obstacles. Having an education opens the door to endless opportunities.

Douglass also had a goal of integrating Rochester public schools. If you look at Rochester public schools, they consist of mainly minorities. This is part of the reason there continues to be an achievement gap between African American and white students. Racial segregation has impacted Rochester by affecting the social and economic aspects of African American people.

Students cannot take full advantage to all of the opportunities if their social and economic status impedes them from focusing fully on their education. Rochester schools need to give students more resources, opportunities, and motivation. Students need to become more motivated and prepared for the next steps in their lives.

Many students aren’t leaving school ready for the next step in their lives. Schools today make college the focus for students after high school. There needs to be a variety of options available for students while they are in still in high school and when they graduate.

In the city, we have programs that prepare students to go into a trade after high school such as vision care, precision optics, culinary arts, and the Teaching and Learning Institute. Schools should offer more programs like these instead of pushing every student to go to college. Many don’t realize that college isn’t for everyone, and I think that schools in the city are slowly realizing that. There is more than one track for education. College is important but it shouldn’t be the only path for quality education and life skills.

I wouldn’t say that Rochester schools have completely lived up to Douglass’s vision yet, but it is definitely a work in progress. Moving forward, schools should offer students more educational opportunities to allow them to gain more experiences. Providing more opportunities will give students a reason to continue coming back to school.

I believe that county-wide magnet programs would be the best way to help reduce the achievement gap in Monroe County and desegregate the public schools. I believe that this will narrow the achievement gap, because African American and minority students wouldn’t be attending homogeneous schools where just about everybody around them comes from an area of high concentrated poverty. Instead they would be at integrated or heterogeneous schools of their choice based on their talents or future careers, where there are people of all economic levels and diverse backgrounds.

Creating county-wide magnet programs would provide a unique range of educational opportunities for students, while combating segregation in schools. This would truly help our schools live up to Frederick Douglass’s vision of a fair, quality education for all.

Taniya Gaines is a senior at East High School.

'Too many students are disconnected from technology'

BY KARY JAMES

today’s children, technology must promote

students working together.” PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

Modern-day technology and the philosophy of one of the greatest minds of the 19th century are not always put in the same sentence. However, the ideas for education by abolitionist and social reformer Frederick Douglass shares initiative set by Rochester city schools to improve education through technology.

Frederick Douglass’s lifelong quest for the liberation of blacks through education included various methods of reaching his audience. He was using multimedia before it was a term, through the publications of books, speeches, debates, and Rochester’s very own newspaper, The North Star. Douglass believed that people can become educated in multiple ways. This idea of versatile education has been adopted by the City of Rochester, and although there have been successes, nevertheless there have also been challenges that must be addressed.

Throughout the late 19th century, despite the abolition of slavery, access to learning was limited for African Americans. Although access has been greatly improved, too many students are disconnected from optimal technology, causing a digital gap. Improving technological equity through functioning Chromebooks, Tablets, and SMART boards would lead to instant progress.

The process of learning anything is not easy; it takes time, repetition, trial, and error. Following the emancipation of blacks, books were around; however, not all people understood how books worked. This barrier stifled progress among freedmen for decades. Similarly, today with technology present and the entire world of information seemingly at our fingertips, a vast majority of students are unaware of the workings of educational software upon initial exposure.

Programming is not always user-friendly and comes with complications causing difficulty for logging in and turning in assignments. If technology were more user friendly, students and families would find the process of learning easier.

Learning is not a process that one does alone, much like winning a championship or running a successful company; it takes a team effort. In many instances, a concept is better understood through a shared perspective. When enslaved blacks learned how to read and set their sights on escaping to freedom, it came through the collective efforts of many blacks and whites on the Underground Railroad. Information was acquired through multiple channels to escape north on the railroad (with Rochester being one of the final stops).

To foster the freedom of today’s children, technology must promote students working together. Students consequently will learn from one another, and they can all share their strengths to accomplish the goal of being better students. Learning games should be cohesive, with elements of competition and increased incentives. Kids will learn from their mistakes and be able to improve their test scores.

History often repeats itself, and methods of learning are no exception. Frederick Douglass’s goal for all people to be better educated and liberated is translated to present time through the use of improvements to multimedia within the classroom. If improvements of access, structure within software, and the continued implementation of interactive team-building software are made, students will have more fun, test scores will improve, people will be more motivated to learn, and most importantly, youth will believe in themselves and their ability to learn.

Rochester city schools are still struggling, but with these improvements even more progress can be made. It does take a team effort. Frederick Douglass said, “If there is no struggle, then there can be no progress,” and while the city has seen its share of turmoil, I believe it will be on the right track soon.

Kary James is a senior at East High School.

‘The status quo is no longer an option’

BY BILL JOHNSON

FILE PHOTO

“What would Frederick Douglass think about the lowly state of the Rochester public schools?” While a popular exercise during this period of commemorating an iconic life, that shouldn’t be our focus. Instead, how are we, the living, going to respond to this crisis?

City schools were functioning reasonably well when my three daughters attended from 1974 to 1992. Not perfectly, but reasonably well. East High School, their alma mater, was frequently cited for the quality of its instruction and student achievement levels. Today, it is trying to reclaim prestige enjoyed 30-plus years ago.

Jaime Aquino, the Rochester City School District’s Distinguished Educator, released a damning report in November on the district’s dysfunctional governance and learning environments. His meticulously documented details confirmed something long overlooked: that the two parties who ought to be working in closest harmony – the school board and the superintendent – have relations that are mostly acerbic, counterproductive, and toxic.

It should not have been that way. I can personally attest to the large number of innovative programs that have been advanced to improve school and student performance. Much time and treasure have been expended. This crisis did not result from a lack of ingenuity or effort.

Since I moved here in 1972, there have been 11 different superintendents, and two have held the position twice. There have been at least two dozen different school board members. We haven’t given proper attention to the disruptive impact this level of churning has had on educational performance. We take for granted that superintendents come and go every three to four years, while board members depart through attrition. Meanwhile, their customers are in the system for 12 or 13 years.

We have had some outstanding superintendents, who have come armed with strategic approaches and innovative ways to engage students, parents, and community leaders. None of them have stayed long enough to see these plans achieve any meaningful impact. Few, if any, have continued an initiative from their predecessors. Passionate board members have brought their own ideas, sometimes in direct conflict with staff.

Much recent attention has focused on school performance data, with scant regard for debilitating structural and organizational issues. The system cannot perform effectively with pervasive levels of disconnection and dysfunction. Students cannot perform competitively if the RCSD’s educational philosophy changes every three years.

There is an immediate set of questions to consider, and two longer-term ones:

1) The board is currently searching for its sixth superintendent in 10 years. What superior candidate will take the job, in such a tumultuous environment? Given that the majority of the board is up for election this fall, is it even appropriate to fill the position now? This search should be suspended, and not resumed until after the elections.

2) On February 8, the district’s response to the Aquino report is due. Its response to the board-superintendent controversy will be instructive. Will it call for major reform, or will it punt? This response will determine whether the district has abdicated its role to lead this discussion.

3) If so, there must be an exhaustive community dialogue to identify new approaches to school governance, including transferring the oversight and evaluation of the superintendent to a new structure independent of the school board. The implications of such a move will be dramatic, requiring a change in the state education law. It will also require adults who proclaim their commitment to improving the quality of public education to give up some real power.

I believe Douglass would tell us that the status quo is no longer an option, and that anything worthwhile is worth fighting for. In the spirit of his fierce advocacy, let this dialogue begin.

Bill Johnson is a former Rochester mayor, former president of the Urban League of Rochester, and the father of former Rochester school district students.