By Vanessa Cheeks and Rebecca Rafferty

We’ve all heard that old adage: Behind every great man there’s a great woman. In some cases, it’s many women bolstering the great man, whether they are mothers, sisters, wives, daughters, colleagues, or friends — and throughout history few of them have been properly credited for their roles. This is certainly the case with the women who aided the endeavors of abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass. A woman taught him to read, a woman helped him escape slavery, women managed his household while he worked, women collaborated with him in the antislavery and women’s movements, and women inspired him with their own accomplishments. Here we take a look at some of the individuals who played important roles in his life.

This is part of a year-long collaboration between Open Mic Rochester and CITY Newspaper.

Harriet Bailey, Frederick Douglass’s mother

Harriet Bailey was enslaved in Talbot County, Maryland. Able to read and write, she had accomplished something most slaves were not able to at that time. Douglass was never able to determine how she came to be literate.

Though Douglass never knew his father — he only knew that he was a white man — it is speculated that Bailey was raped by her master at the Holmes Hill Farm. She gave birth to Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in 1818. Frederick, whom she called “my valentine,” was transferred to the Wye Plantation to live with his grandmother, giving Bailey more time to work in the fields. She would periodically travel the 12 miles after working the Holmes Hill Farm to see her young son, and she was still required to be back for work the following morning.

The trip was difficult and Bailey was only able to see Frederick between four or five times before she died, when he was 7 years old. She also had 5 other children: Sarah, Eliza, Kitty, Arianna, and Perry.

Bailey died in 1825. After escaping from slavery, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey changed his name to Frederick Douglass, and though he never knew his exact date of birth, chose February 14, 1818, as his birthday in honor of his mother.

Anna Murray-Douglass, Douglass’s first wife

Anna Murray was born in 1813 in Denton, Maryland, the youngest of eight children and the only sibling born free. As a teen she worked as a laundress and housekeeper in Baltimore, and became uncommonly wealthy and independent at a young age. Her freedom and success inspired Douglass — whom she met at the docks where he worked while she was taking in laundry — and she helped him escape in 1838 by giving him sailor’s clothing and a portion of her savings. He boarded a train to Philadelphia and then to New York City, where Murray joined him. They were married in September, and within 10 years had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass, Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass.

While Douglass built his career, Murray-Douglass managed their household wherever they lived and supported him financially by working as a laundress and making shoes. She was an activist in her own right, taking part in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, a short-lived organization that established national women’s conventions, organized a multi-state petition campaign, sponsored successful fundraisers, and sued Southerners who brought slaves to Boston. When the Douglass family relocated to Rochester, she established an Underground Railroad headquarters in their home and provided shelter and meals for fugitive slaves on their way to Canada.

Despite her role in his life and their 44-year-long marriage, Murray-Douglass was barely mentioned in Douglass’s three autobiographies. His lengthy travels as a lecturer and activist, and the higher social circles he moved within, may have contributed to a sense of estrangement between the two; it’s thought that because she never learned to read and write fluently, she felt she didn’t fit in.

Murray-Douglass died of a stroke in 1882 at the family home in Washington, DC, where she was buried at Graceland Cemetery. When that cemetery closed she was moved to Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester two days before Douglass died in 1895. He was buried next to her. In “Anna Murray Douglass, My Mother As I Recall Her,” the Douglass’s daughter Rosetta Douglass Sprague wrote that her father’s story was “made possible by the unswerving loyalty of Anna Murray.”

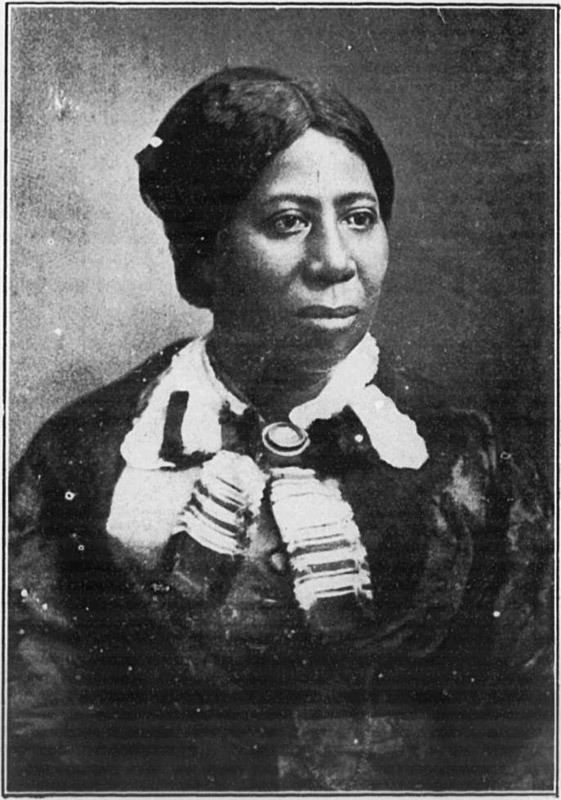

Ida B. Wells, fellow abolitionist

Ida B. Wells was born July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, to enslaved parents just six months prior to the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. She attended Shaw University (then called Rust College) but was expelled after a confrontation with the school’s president. Around this time she lost both parents and one sibling in a yellow fever outbreak.

Best known for her anti-lynching activism, Wells was also a pioneer of black investigative journalism. Using data collected through her extensive research, she was able to paint a picture of the plight of the African-American with undeniable numbers and facts. In her early 30’s, she published her first book, “A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings In the United States.” Wells also fought segregation, organized boycotts of white-owned businesses, and pushed for black Americans to move to more progressive parts of the nation.

Frederick Douglass praised Wells’s work in an 1892 letter: “Brave Woman! You have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured.”

Wells fought not only with her words but with action, once biting a man who attempted to remove her from a train after she refused to sit in the black car. She also purchased a pistol after the lynching of three friends. “I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap,” she wrote in her unfinished autobiography, “Crusade for Justice.”

Wells died in Chicago at age 68 on March 25, 1931.

Helen Pitts Douglass, Douglass’s second wife

Helen Pitts was born in 1838 in Honeoye, New York. After graduating in 1859 from the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College), she taught at the Hampton Institute in Virginia before moving to Washington, DC. Her family home was located next door to Cedar Hill, the home of Frederick Douglas, and she soon began supporting his work as a clerk in his office.

Pitts was hired by Douglas directly to work with him at the office of the Recorder of Deeds. An experienced abolitionist and co-editor of feminist newspaper The Alpha, she used her expertise to assist Douglas as he authored his third autobiography, “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.”

Pitts and Douglass married in January of 1884 to much resistance from her white family. Although her family were well-known abolitionists, they disapproved of her marriage because of Douglass’s mixed lineage. Eventually, she was disowned by her own relatives. Douglass’s children — specifically his daughter Rosetta — also disapproved of their union, believing his relationship with a white woman disrespected their deceased mother’s legacy and his own.

After Douglass’s death in 1895, Pitts spent her final years campaigning to preserve their Cedar Hill property as a memorial to her late husband. At her request and with her hard work, in 1900 Congress chartered the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, which was organized to honor Douglass while preserving the legacy of the anti-slavery movement in the United States.

Pitts died in 1903 in Washington, DC, and was buried next to Douglass at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.

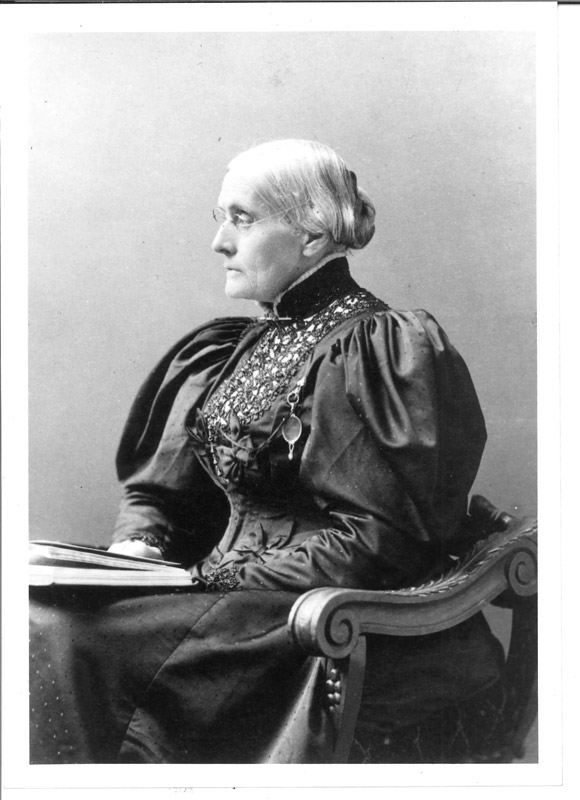

Susan B. Anthony, fellow abolitionist and friend

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, to Quaker parents in Adams, Massachusetts. One of the most noted abolitionists and suffragists, Anthony spent her life fighting for these and other causes.

In 1845 the Anthony family relocated to a Rochester farmhouse, which became a central hub in the fight against slavery. It was there she began her work with Frederick Douglass, and the two often collaborated on key issues and worked together to develop one another’s platforms.

While she worked alongside suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton to produce the weekly women’s rights newspaper, The Revolution, the 15th Amendment was ratified by Congress, giving black men the right to vote before women gained suffrage. This landmark decision created a rift between Anthony and Douglass, forever altering their friendship.

While Douglass fully supported the Women’s Rights Movement, he believed any progress in the name of empowering the disenfranchised was still progress. In an 1869 meeting of the American Equal Rights Association, Anthony walked out after an argument with Douglass highlighted their differences. Though this was not the end of her work with Douglass, she went on to form the National Woman’s Suffrage Association with Stanton and her supporters.

Anthony died March 15, 1906, in her Rochester home, and is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery.

Suggested reading:

“Women in the World of Frederick Douglass” by Leigh Fought

“Anna Murray Douglass, My Mother As I Recall Her” by Rosetta Douglass Sprague