Rochester likes to claim

Frederick Douglass as its own.

Is the community living up to his legacy?

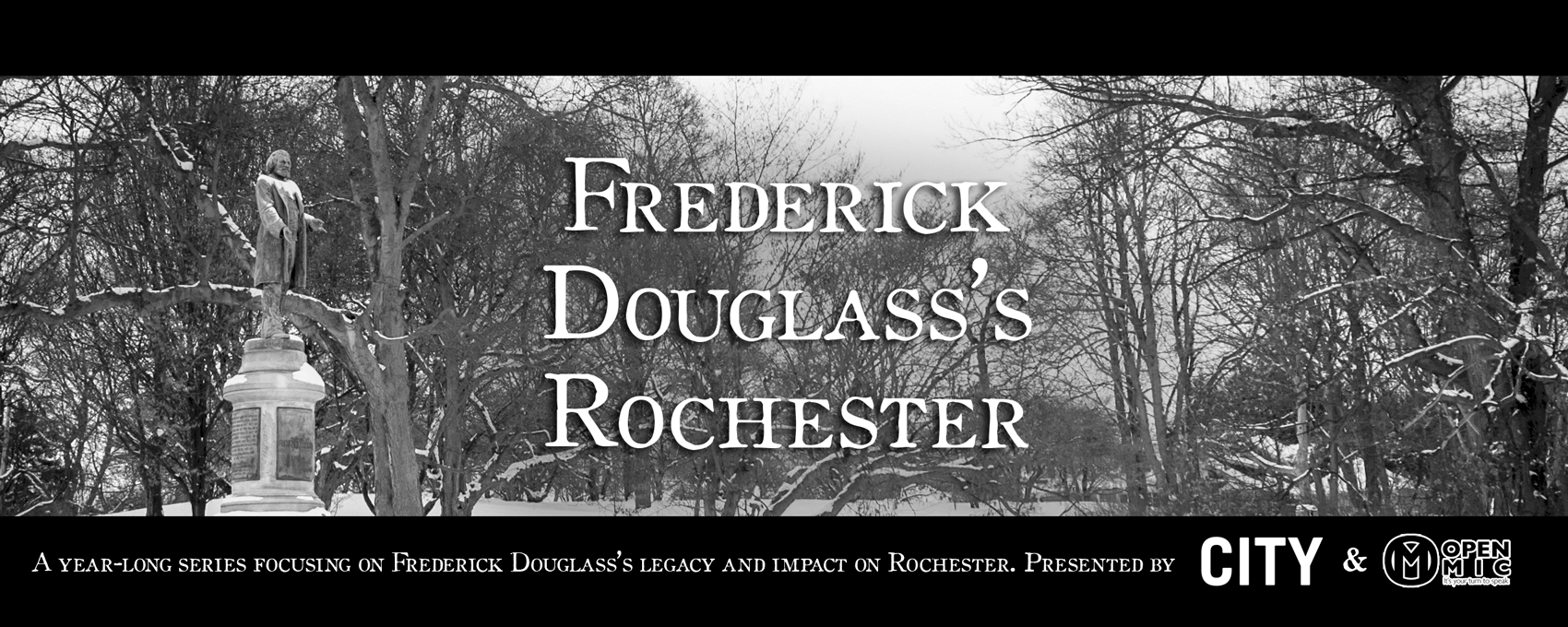

First in a year-long quarterly series on Frederick Douglass and the issues he championed, produced by Open Mic Rochester and CITY Newspaper. Both publications will also have related articles throughout the year.

By Tianna Mañón and Jake Clapp

The first monument in the United States dedicated to a black citizen is of Frederick Douglass, and it’s located in Rochester. The 8-foot-tall bronze statue stands on a 9-foot granite pedestal at the upper edge of the Highland Park Bowl.

Its original location, when it was unveiled on June 9, 1899, was downtown, at Central Avenue and St. Paul Street, near the New York Central Railroad Station. And so one of the first things people saw as they came by train into Rochester was the figure of Douglass mid-speech, hands open and out, his right foot slightly forward, addressing the gathered crowds — his “favorite and most effective pose,” as John W. Thompson says in his 1903 book, “An Authentic History of the Douglass Monument.”

“To place a monument of an African-American in front of the train station, so all the world could see that Rochester’s greatest citizen was not a white man, that has to tell you everything you need to know about the impact he had on culture,” says Carvin Eison, project director for “Re-Energizing the Legacy of Frederick Douglass,” a multi-organization initiative to commemorate Douglass’s life this year.

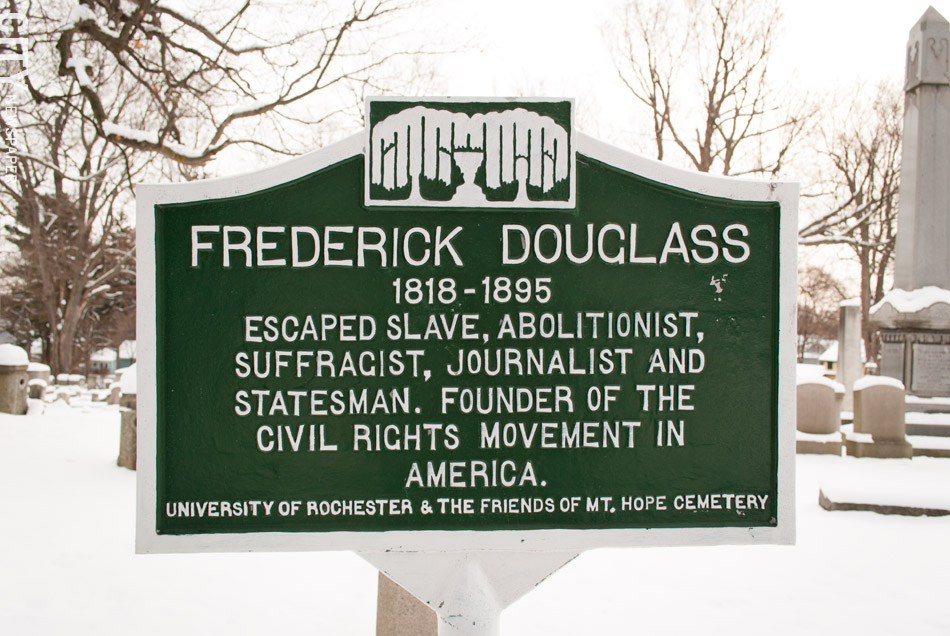

Douglass — who was born into bondage, took his freedom, and became one of the most prominent men of the 19th century — made Rochester his home for 25 years, arguably the most active and important of his career, and he is buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery.

February 14 this year is the 200th anniversary of the birth date Douglass chose for himself, and Rochester arts and cultural organizations, civic groups, artists, politicians, and activists have planned a year of exhibits, discussions, and events as a way to reflect on Douglass’s legacy. Along with the “Re-Energizing the Legacy” project, the City of Rochester and Monroe County officials have declared 2018 “The Year of Douglass,” and the city is using a new official Flower City logo that incorporates a portrait of Douglass.

The anniversary presents an opportunity. Rochester likes to claim Douglass as its own, but in a community where inequality and racism continue to oppress people of color, his legacy hasn’t been used as a guiding force to shape real progress.

Numerous events in 2018 will celebrate Douglass’s life, but “Re-Energizing the Legacy” organizers hope the event will lead the community to go further — that Rochester will have needed conversations about race and similarly complicated issues that Douglass himself faced, Eison says.

Rochester faces serious problems, including racism and discrimination, which are very much alive in the region. As ACT Rochester’s “Hard Facts: Race and Ethnicity in the Nine-County Greater Rochester Area” report stated last August, in the nine-county Greater Rochester area there are “substantial disparities” between African-American and Latinx communities and white populations in poverty, academic achievement, earnings, and homeownership.

African-American income levels are only 48 percent of those of white residents. White Rochesterians are more than twice as likely to own homes as African-Americans and Latinx are. “Disparities begin at birth and continue through childhood,” the report says, and success in school is “highly correlated with race and ethnicity.” More troubling, those outcomes are worse in Rochester than in New York State or the nation as a whole.

“We have to be purposeful” about living out the vision and intent of Douglass and other activists of the period, says the Reverend Derrill Blue, pastor at Rochester’s Memorial AME Zion Church, the church the Douglass family attended. “We have to understand their time and what’s still an issue. Address that today. What we want to avoid is repeating the past. If we don’t learn lessons, the past will be our present.”

Douglass was a self-made man — although in his own words, “Properly speaking, there are in the world no such men as self-made men” — and during his 77 years, he became an internationally known abolitionist, suffragist, newspaper publisher, lecturer, and statesman. His life intersected with President Abraham Lincoln (and with almost every successive US president until Douglass’s death), Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, John Brown, Ida B. Wells, and countless other influential people of the period. Through three autobiographies, a novella, almost 50 years of journalism, what are most likely hundreds of speeches, he championed freedom and equality.

Douglass was a self-made man — although in his own words, “Properly speaking, there are in the world no such men as self-made men” — and during his 77 years, he became an internationally known abolitionist, suffragist, newspaper publisher, lecturer, and statesman. His life intersected with President Abraham Lincoln (and with almost every successive US president until Douglass’s death), Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, John Brown, Ida B. Wells, and countless other influential people of the period. Through three autobiographies, a novella, almost 50 years of journalism, what are most likely hundreds of speeches, he championed freedom and equality.

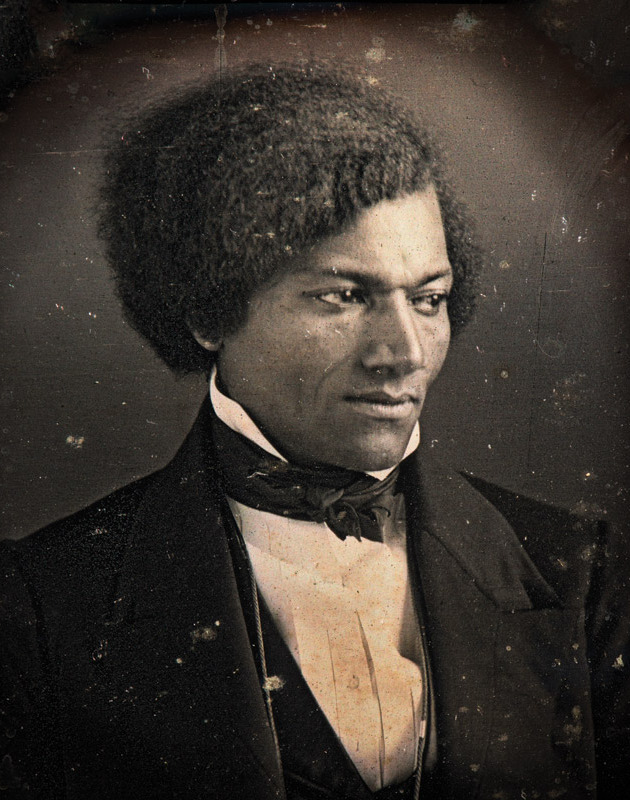

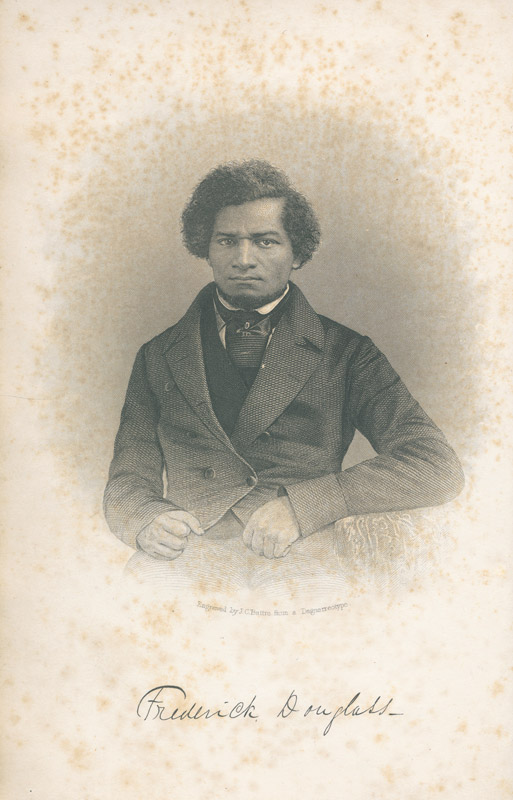

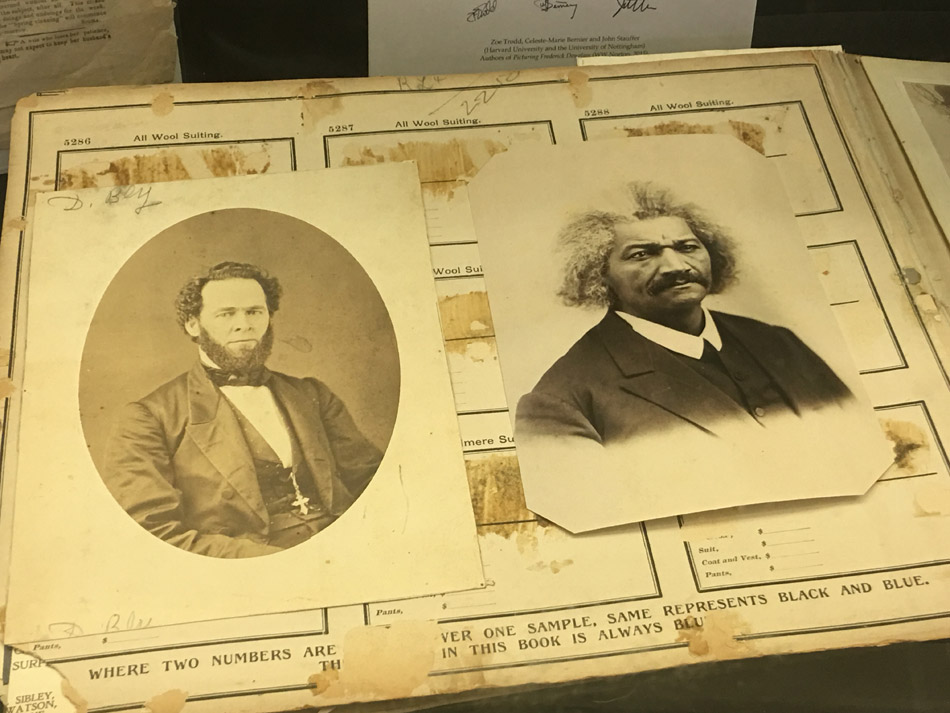

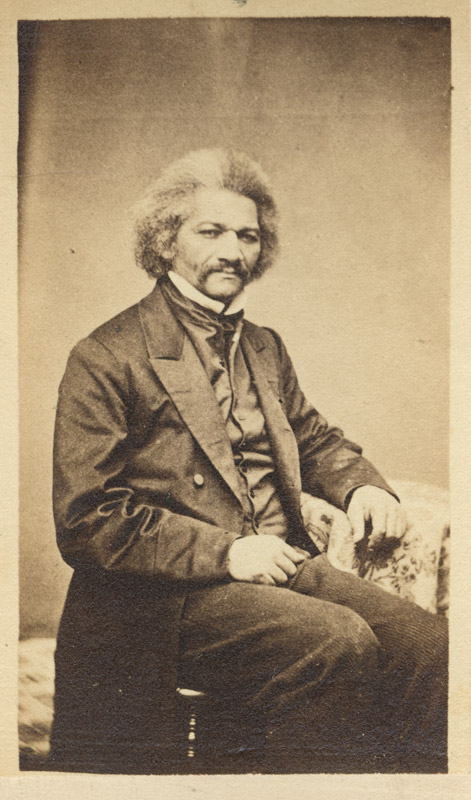

And in an interesting coincidence for the home of George Eastman and Kodak, Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century, with 160 separate photographs. He believed in the truth-telling power of the medium and used it as a tool to further his work. (The George Eastman Museum, however has only one photo of Douglass in its collection.)

Douglass wasn’t just a great orator, says David Shakes, director of the Rochester theater company The North Star Players, he was philosophic and analytic in his writings and speeches. “He looked at religion, politics, economics, trade, the church,” Shakes says. “He really went into different systems and addressed them and gave an analysis.”

He saw the power of using the press “to put things into the court of public opinion to press for equality, dignity, and integrity in our country,” Shakes says.

Shakes has been portraying Douglass as part of living history tours and in plays for around 35 years. His first time was at Douglass’s gravesite in Mt. Hope Cemetery — the experience was “electrifying,” Shakes says — and his company recently staged the multidisciplinary production “No Struggle, No Progress” at MuCCC.

Douglass’s call was to “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!” and he used humor, sarcasm, and colorful rhetoric, Shakes says, to grab his audience’s attention.

“His words are so relevant today,” Shakes says. “Prophetic. His words fit our situation, and it gives you reason to pause and to think, and to spur you into action.”

Douglass was born into bondage in 1818 as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. He never knew his true birthdate, but later chose February 14. He took his freedom on September 3, 1838: Carrying a friend’s Seaman’s papers, he boarded a train in Baltimore and escaped north by boat and train. Within 24 hours he was in New York City and on free soil, though not yet legally a free man.

During his short time in the city, Anna Murray — a free black woman whom Frederick had met in Baltimore — joined him, and the two were married. They were together for 44 years, until Anna’s death in 1882.

Frederick’s life “was a story made possible by the unswerving loyalty of Anna Murray,” their oldest child, Rosetta Douglass, said in a speech decades later. “Her courage, her sympathy at the start was the main-spring that supported the career of Frederick Douglass.”

Frederick and Anna quickly moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Frederick chose a new name: Frederick Douglass. In New Bedford, Douglass joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, serving as sexton, clerk, and class leader. The church’s pastor, the Reverend Thomas James, formerly of Rochester, was instrumental in urging Douglass to speak out about slavery — and almost certainly told Douglass about the frontier town on the Genesee River.

Douglass increasingly began to use his rich baritone voice to speak about abolition, and in August 1841 he met William Lloyd Garrison at a New Bedford Anti-Slavery meeting. Garrison, who was editor of the prominent abolitionist publication The Liberator, invited Douglass to speak before the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass told his personal story and moved the crowd, which invited him to become an agent for the society. He began giving lectures on a circuit, including in Rochester in 1843.

“He was at any one time the smartest, most charismatic person in the room,” says Jose Torre, SUNY Brockport history department chair and history consultant for the “Re-Energizing the Legacy” project. “Douglass was blowing away the Garrisonians. People wanted to see and hear Douglass. All these other speakers were second-rate compared to Douglass.”

Douglass quickly emerged as a leader in the anti-slavery movement, and became well known with the 1845 publication of his first autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” But success was a double-edged sword, and Douglass was in danger of being captured by slave hunters. For slaves, getting to the North didn’t translate to true sanctuary; if a slaveholder offered money for runaways, there were often people chasing them down, and the North didn’t prevent their being returned. Slaves, after all, were considered property. Those sentiments would later be codified in the Fugitive Slave Act, which legally sanctioned the capturing and return of runaway slaves.

So Douglass traveled to the British Isles for 18 months on an anti-slavery lecture tour. While in England, new friends raised $711.66 to buy Douglass’s legal freedom.

He returned to the US in 1847 with $4,000 in contributions from English abolitionists, who urged him to start his own anti-slavery newspaper. But the endeavor was met with opposition by Garrisonian abolitionists.

Douglass wasn’t deterred. He “had to become his own person,” Torre says, “and was looking for a new kind of philosophical platform for anti-slavery.”

“From motives of peace,” Douglass wrote in “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” his third autobiography, “instead of issuing my paper in Boston, among New England friends, I went to Rochester, New York, among strangers.”

As a riverside city with several mills, Rochester was quickly becoming a “Boom Town,” with large influxes of new residents — many from the northern US. According to Milton Sernett’s 2001 book “North Star Country,” “the mass moving of ‘Yankee’ or Northeastern Quakers into the area paved the way for the city’s liberal leanings.”

By the time Douglass moved to the city, there was already an active black community. Because of its reputation as a progressive city, Rochester was widely considered a place where black people could get further ahead than elsewhere in the country.

And the numbers show it: an 1834 survey counted 360 people of color in a total Rochester population of about 9,000. And according to Sernett, there were 655 free black people in Monroe County in 1840, and about 605 by 1870 (the decline due to the impact of the Civil War).

Rochester also had a large and powerful black church community. Church members fought for better treatment and rights and worked to advance the black community socially and economically.

“It became a sanctuary, a gathering place for the community to come together,” AME Zion’s Derrill Blue says. “Whatever issue it was, they gathered there.”

Douglass was heavily involved with the church and often spoke at AME Zion, Blue says: “That’s how he actually worked on his oratorical skills. He used the church as a place to shape him and to finesse how he presented what he said. It’s beautiful to see how he used his gifts in the church and in society.”

According to Sernett, Douglass’s home and the church were both stops on the Underground Railroad, and Douglass worked with the church to help people seeking their freedom coming through the area. And he published the first copies of his newspaper in the basement of AME Zion. He later moved the offices to the Talman Building on Buffalo Street (now 25 East Main Street), where his newsroom was housed for several years. Today, that spot is marked with a plaque.

The North Star was one of Douglass’s major accomplishments. According to Will Fassett’s essay “The North Star, 1847-1849,” the abolition paper circulated predominately in New York State, but it was also popular in nearby Connecticut and Massachusetts and had some distribution in Michigan. Problems with infrastructure and the high cost of mailing newspapers meant The North Star didn’t go much further than that, but copies did find their way to California and Central Texas.

In the first few months of the North Star, Douglass struggled to meet the cost of printing. The paper’s prospects, he said then, were “far from encouraging.” He’d received an initial investment from British supporters and the Posts, a wealthy Rochester family, but half of that went toward a printing press, and the remainder was quickly disappearing.

“In 1848 the cost of printing each week was approximately $20,” says Fassett, and Douglass’s subscriptions amounted to just $25 weekly on average. Douglass was forced to ask for more donations and increase the subscription price. Despite the challenges, he was able to get subscriptions up to 7,000 at one point, according to his records.

Along with publishing The North Star, Douglass delivered some of his most powerful speeches at this time, including “What to a Slave Is the 4th of July?” given at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall on July 5, 1852. The address, one of his most celebrated, condemned the hypocrisy of a national holiday celebrating independence while slavery was still an American institution.

Soon after moving to Rochester, Douglass also committed himself to women’s suffrage and became life-long friends with Susan B. Anthony — although a tense split over priorities developed for a period between the reformers following the Civil War.

Given his accomplishments, Douglass can be relegated to the status of a legend. “I think one thing that’s really important is just remembering his humanness,” says City Historian Christine Ridarsky. “Sometimes figures like Douglass get put on a pedestal, and we forget they’re human beings.”

This is a man who survived slavery, Ridarsky says. But he was also “a man who walked the streets of Rochester on a regular basis, asked people how’s it going.”

For his first four years in Rochester, Douglass lived on Alexander Street, near what is now East Avenue. However, as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, he needed a home more conducive to hiding and moving people in bondage. He built a new home on land located on what’s now South Avenue (where School 12 stands today) — a more secluded area with a private road and no neighbors. There, he, Anna, and their children (Rosetta, Frederick Jr, Charles, Lewis, and Annie) lived for more than two decades.

Like Douglass, Anna worked with the Underground Railroad, in addition to managing their home and property while Douglass continued his work as a journalist, orator, and abolitionist.

Among Douglass’s acquaintances during that period was the abolitionist John Brown, whom Douglass had known since 1847. Brown stayed with the Douglasses in Rochester several times, and he had shared with Douglass his plans of an attack on the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia.

In October 1859, just before the raid, Douglass met Brown and his men in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and withdrew his support for the effort, believing it would fail against the government forces. As he predicted, the raid was unsuccessful. Brown became known as a martyr for freedom — and Douglass learned he was wanted as part of the conspiracy. He escaped to Canada following one of the Underground Railroad routes, and then went to Britain until it was safe to return. While he was there, on March 1, 1860, less than two weeks from her 11th birthday, his youngest child Annie died, a tragedy that would cast a shadow over the family the rest of their lives.

Prejudice in the early 1840’s in Rochester, daughter Rosetta said later, “ran rampant,” and Rosetta experienced it first hand. Black students weren’t allowed to attend Rochester public schools, and rather than enroll her in the black school, the Douglasses sent her to an all-girls private school. But Rosetta was segregated from the other students, forced to be taught in a separate classroom. When Douglass found out, he confronted the teacher and the class. The students themselves said they’d be willing to sit by Rosetta, but school officials then turned to the students’ parents. One parent objected, and the school kept the class segregated.

In a column in his newspaper, Douglass slammed school officials and called for the integration of local schools — 100 years before Brown v. Board of Education.

“Meanwhile I went to the people with the question and created considerable agitation,” Douglass later wrote. “I sought and obtained a hearing before the Board of Education, and after repeated efforts with voice and pen, the doors of the public schools were opened and colored children were permitted to attend them in common with others.”

As the home of Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, and others, Rochester has long been considered a progressive city. But “the majority of North Star Country Christians were neither openly hostile to abolitionists nor widely enthusiastic,” Sernett writes.

“The entire city, entire community was never as progressive as we make it out to be,” Ridarsky adds. “If you look at attitudes toward abolition, 14th and 15th Amendments, and even beyond that, there was a lot of opposition here in Rochester.” The amendment to the state constitution that gave New York women the right to vote in 1917 was voted down in Monroe County.

In the mid- and late-1800’s, nationalistic white Americans, seeing a rise in European immigration, an increase in black wealth, and a perceived threat to their own wealth, wanted to retain their financial and political stronghold. In the South, black voters were being intimidated and disenfranchised, and the Ku Klux Klan was formed. Prejudice and hate were not confined to Southern states, however.

Locally, Germans and Italians were beginning to move to the city, and the black community was growing. Racial tension between groups of Rochester residents is not new, Ridarsky says. “There’s really no place immune to those things.”

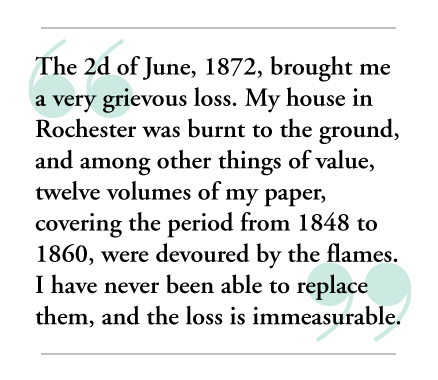

On June 2, 1872, the Douglass home on South Avenue burned. While no one was injured — Douglass himself was in Washington, DC, at the time — the house, barn, and many of the family’s possessions were destroyed. A definitive explanation for the fire has never been known, but it’s commonly believed to have been the work of an arsonist. The fire had started in the barn, but no one in the family had used a lantern or fire in the building for months, and Douglass himself blamed racial tensions in the area.

“It was never proven to be arson, but there was certainly suspicious circumstance,” Ridarsky says. “There was certainly racial tension during that time period and discomfort in the community that had risen over time.”

Ridarsky says Douglass used the arson to spread his message further and as a way to discuss racial tensions locally and nationally.

In a letter to readers in his newspaper, The New National Era, Douglass said he could not guess as to the motive behind the fire, but, he wrote: “One thing I do know, and that is, while Rochester is among the most liberal of northern cities and its people are among the most humane and highly cultivated, it nevertheless has its full share of that Ku Klux spirit which makes anything owned by a colored man a little less respected and secure than when owned by a white citizen.”

Adding to the insult, Douglass was turned away from two hotels when he rushed into Rochester at 1 a.m. — “with the convenient excuse that ‘We are full,’ till it was known that my name was Frederick Douglass, when a room was readily offered me, though the house was full! I did not accept, but made my way to the police headquarters, to learn, if possible, where I might find the scattered members of my family. Such treatment as this does not tend to make a man secure in either his person or property,” he wrote in his letter to readers.

Even the fire was originally blamed on a person of color, according to Ridarsky and a Rochester Union and Advertiser article written around the same time. “The testimony thus far obtained points strongest to colored persons as the guilty party,” the article says. But there was little evidence of this, Ridarsky says, and more likely was “convenient speculation.”

The fire at Douglass’s home is a part of his story in Rochester that isn’t explored often enough, Carvin Eison says. There isn’t a lot of discussion about the significance of the event or information about any investigation — whether it was intentional or even accidental.

“That’s difficult for people to talk about, and difficult for people to address,” Eison says, “because that sort of acknowledges some of the worst parts of the tensions between African Americans and the dominant culture, particularly in the 19th century.”

Twelve volumes of Douglass’s newspaper, covering 1848 to 1860, along with invaluable personal letters, were lost in the fire. “If I have at any time said or written that which is worth remembering or repeating, I must have said such things between the years 1848 and 1860, and my paper was a chronicle of most of what I said during that time,” Douglass later wrote in “Life and Times.”

This loss is a large reason why scholars have a hard time painting a complete picture of Douglass’s time in Rochester, says Larry Hudson, an associate professor of history at the University of Rochester. Douglass’s biographies and his speeches are useful, but they mainly offer his analysis and thoughts, and were written for an audience that would have been interested in the fight against discrimination and didn’t necessarily care about his life in Rochester.

“We don’t have the kinds of sources historians rely upon to write the kind of study of a person and a place that readers demand today,” Hudson says.

The destruction of Douglass’s home of 20 years closed the Rochester chapter of his life.

Following the Civil War, Douglass was beginning to spend more time in Washington, DC, and his focus was turning toward voting rights. In 1870, he began publishing the DC-based New National Era, a national paper for black Americans. Following the burning of his home in 1872, Douglass decided to move to DC full-time, first living on Capitol Hill and then in 1878, moving to an estate he called Cedar Hill in Anacostia, a DC suburb.

Along with publishing The New National Era, Douglass served in several governmental positions: Commissioner to report on annexing Santo Domingo; Marshal of the District of Columbia; Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia; and Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti. He did return to Rochester during that time, though, including in 1892, when he and President Benjamin Harrison dedicated the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Washington Square Park.

In 1882, Anna Douglass suffered a stroke and died. About 18 months later, Douglass married Helen Pitts, an abolitionist and suffragist from Honeoye. Pitts was white, and the marriage caused controversy and upset both families. (The marriage is another part of Douglass’s story that Carvin Eison believes is under-explored.)

After Douglass’s death, Helen was instrumental in preserving his legacy. His home at Cedar Hill is now a national historic site, and Helen established the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, an Easton, Maryland-based non-profit maintaining Cedar Hill, Douglass artifacts, and history of the anti-slavery movement.

On February 20, 1895, following a day spent at a meeting of the National Council of Women, Douglass was at home with his wife, telling her about the meeting — “in the highest spirits,” the New York Times wrote in its obituary — when he dropped to the floor. He died within minutes.

Douglass’s body lay in state in Washington, and a funeral service was held there at the Metropolitan AME Church, where Susan B. Anthony delivered a eulogy. But his final resting place wouldn’t be in the nation’s capital; it would be in Rochester, in Mt. Hope Cemetery.

In Rochester, Douglass’s body again lay in state, at City Hall. Public school classes were dismissed early, and thousands of people passed through to pay their respects. A public funeral was then held at the city’s largest church, Central Presbyterian, now Hochstein School of Music and Dance.

“Every seat and every available bit of standing room in the great church was occupied when the services began,” John W. Thompson later wrote. The crowd followed the hearse to the gates of the cemetery, and Douglass was laid to rest next to his first wife, Anna Murray, and his youngest daughter Annie. Helen Pitts was buried next to Douglass following her death in 1903, and Rosetta Douglass Sprague and her husband, Nathan, are also buried in Mt. Hope.

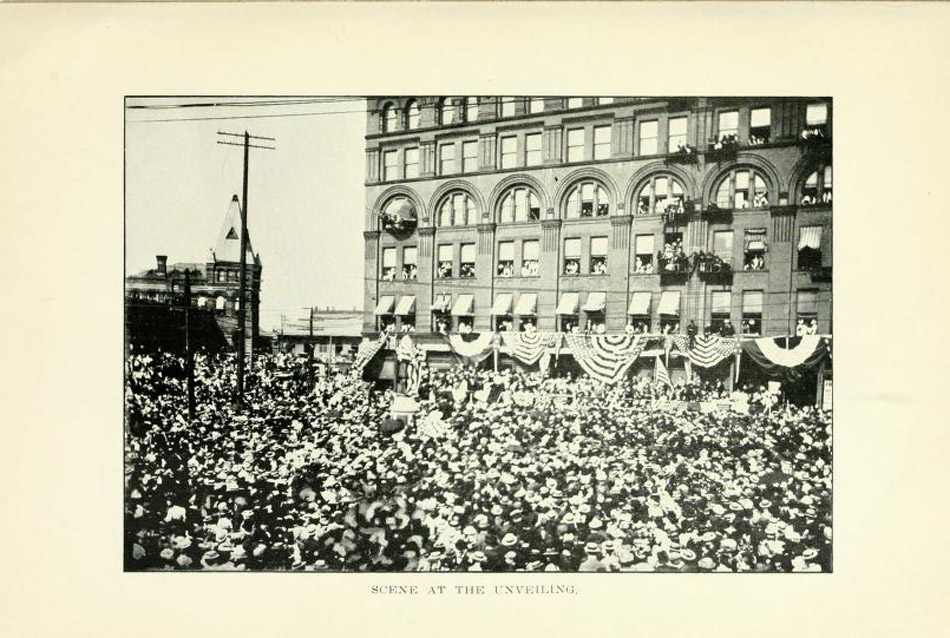

When news of Douglass’s death reached Rochester, John W. Thompson led the charge for creation of a monument. Thompson, along with a committee formed at a Eureka Lodge meeting, had actually started a project in 1894 to erect a monument to African-American soldiers and sailors who had died in the Civil War. And Douglass had enthusiastically supported that monument. But upon Douglass’s death, the committee decided that the monument would honor him.

When money had been raised and the statue was ready — sculptor Sidney Edwards used Douglass’s son, Charles, as the model — the monument was unveiled at Central Avenue and St. Paul Street in 1899 to a crowd of about 10,000 people. Theodore Roosevelt, then New York State governor, addressed the crowd, and letters of support came in from numerous prominent figures, including Booker T. Washington and President William McKinley. The government of Haiti — a nation established after a successful slave revolution — donated $1,000 toward the monument.

The statue’s placement near Rochester’s railroad station “really says something about how his legacy was upheld at first,” Ridarsky says. “It was right smack dab where anyone coming into the city was confronted with this very powerful image of an African American.”

Tributes to Frederick Douglass have been woven throughout Rochester. But his memory is kept alive in more subtle ways, rather than serving as a prominent guiding force for the community. There’s the Douglass-Anthony Bridge spanning the Genesee River. The University of Rochester has a Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American studies, a Frederick Douglass Commons, and a Douglass Leadership House, and an 1879 bust of Douglass is in Rush Rhees Library.

The city’s South Avenue library branch, on the site of Douglass’s destroyed home, was renamed the Frederick Douglass Community Library in 2016. And School 12, part of the same building complex, has a marker with details about Douglass and the site. But the school is named for the 20th century politician James PB Duffy.

Some local artists have incorporated Douglass into their work. Among the examples: Shawn Dunwoody’s Douglass portrait under I-490 at West Main Street, alongside Nathaniel Rochester, Austin Steward, and Anthony, and sculptor Pepsy Kettavong’s statue of Douglass communing over tea with Anthony, in the park in the Susan B. Anthony neighborhood.

Douglass’s name has popped up in various other local tributes, sometimes in curious ways. (Is Three Heads Brewing’s “Freddy D” beer the best way to commemorate the life of a man who endorsed temperance?)

Grassroots organizations and activists have carried on Douglass’s work in their own missions, but there hasn’t been a mainstream awareness of Douglass’s legacy or of Rochester’s place in his life. It’s important for the community to embrace his legacy and to make sure that it’s promoted outside the area, says City Historian Christine Ridarsky. “People should be flocking to Rochester to learn about Frederick Douglass,” she says.

In the first few decades of the 20th century, there appears to have been occasional commemorations to Douglass. But in the post-war era, focus on Rochester’s African-American history seemed to fade. And at the same time, inequality was growing in Rochester.

“It’s surprising how little was being said about him in the 1950’s and 60’s,” says Dr. David Anderson, a member of the national Frederick Douglass Bicentennial Commission and chair of the Rochester-Monroe County Freedom Trail Commission.

It’s hard to know why there wasn’t more focus on Douglass during that period, Anderson says, but serious issues were dominating Rochesterians’ attention. Migration from the Southeast quickly increased Rochester’s black population, and by the 1950’s, black unemployment was at 10 percent (compared to about 2 percent among whites). Discrimination kept black residents from participating as heavily in the local economy, and there are hundreds of reports of the overcrowding and low-quality housing. Those who were able to find work and save for a home were often restricted to certain areas, where the housing stock was of lower quality, and were denied credit and insurance.

City leaders weren’t paying much attention to the problem of the housing conditions, however. High-profile clashes between black citizens and police began to occur, and things hit a boiling point with the riots of July 1964.

“You have all of these issues, which are distracting people from looking into the history,” Anderson says.

But since the Freedom Trail Commission’s creation, interest in Douglass and in Rochester’s Underground Railroad history has been gradually increasing. The Freedom Trail Commission announced a “Year of Frederick Douglass” in 2003, and toward the end of that year, the Rochester Museum and Science Center opened “Rochester’s Frederick Douglass,” at that point, the largest exhibition ever presented on the abolitionist.

Anderson says there’s a need for more attention to Douglass, especially in the public school system. But, he says: “I’m hoping we’re on the right track now, and we’ll take our rightful place, given that the 20-something years the family lived here outpaces any other place they’ve been.”

Contemporary Douglass scholars have plenty of ideas on how Rochester could better promote Douglass’s legacy. UR history professor Larry Hudson says scholars could do more to focus on Douglass’s place in Rochester and to promote their research to the wider public. And politicians and government leaders should better work with those scholars to make that history public, to drive the point of Rochester as the primary home for Douglass.

There’s also a need for a well-supported Douglass center. David Shakes hopes for a “focal point where you could have discourse and exhibits and interactive activities going on related to the vision of Douglass and the vision of a higher moral bar being strived for,” he said.

(There have been at least two attempts at a Douglass center locally: the Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center in the 1990’s and the Frederick Douglass Resource Center on King Street, which was open from 2009 to just last year.)

For 25 years, Douglass called Rochester home. “I now look back to my life and labors there with unalloyed satisfaction, and having spent a quarter of a century among its people, I shall always feel more at home there than anywhere else in the country,” he wrote in his final autobiography, “Life and Times.”

But Rochester has constantly struggled with its progressive and repressive aspects, Shakes says. “I think now is the time to show that we need to hold fast and try to put some things into action that were stated by Douglass and projected by him. We have a lot of work ahead of us. We’ve come a ways, but we have a long ways to go.”