A long list of problems is suppressing voter turnout in New York State

By Jake Clapp

Part of a year-long, quarterly series examining how Rochester lives up to the legacy of Frederick Douglass, produced by Open Mic Rochester and CITY Newspaper. Both publications will also have related articles throughout the year.

Frederick Douglass knew the power of the ballot. While the abolition of slavery had been his main focus for decades, Douglass often spoke and wrote about enfranchisement. Equality, he said, for both black Americans and women, must include the ability to vote and to have a hand in making and administering the laws of the land.

After the Civil War ended and the institution of chattel slavery was abolished, Douglass set out on his next steps: uplifting the recently emancipated and helping lead the fight for equality. Douglass believed that there was no safety for formerly enslaved people — many of them living in hostile conditions in the post-Civil War South — outside of recognition and protection by the American government. To “guard, protect and maintain his liberty, the freedman should have the ballot,” Douglass wrote in his autobiography “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.”

“Hence,” Douglass wrote, “regarding as I did the elective franchise as the one great power by which all civil rights are obtained, enjoyed, and maintained under our form of government, and the one without which freedom to any class is delusive if not impossible, I set myself to work with whatever force and energy I possessed to secure this power for the recently-emancipated millions.”

Voting is the basis of the American political system. But it has also been one of the system’s most contentious parts. Every group in the country’s history, except for white, land-owning men, has had to fight for its right to the ballot box. Today, restrictive measures continue to suppress voter turnout across the country.

New York isn’t one of the states that have enacted ways that actively restrict voter access, like voter ID laws. But a complex list of problems does help suppress voter turnout. In 2016, New York ranked 41st in the nation in voter turnout, with a 57 percent voting rate. (Monroe County did beat that, with 76.3 percent.) During the 2017 general election, 38.2 percent of registered Monroe County voters went to the polls; turnout in the city of Rochester was 30.6 percent.

“We’re not like Southern states, where they’re constantly fighting over voter ID and that sort of disenfranchisement,” says Jennifer Wilson, director of program and policy at the New York League of Women Voters. “But in New York State, we’re definitely not in a good spot.”

Voter suppression in New York can’t be attributed to a single barrier. Voting rights advocates point to a long list of actions and rules that dissuade people from voting, from requiring an excuse for absentee voting and needlessly early voter-registration deadlines to gerrymandering. And voter apathy adds to the problem.

In May, the New York Senate Democratic Conference released the results of a survey it conducted to determine reasons people didn’t vote. The survey polled 930 eligible New York voters, and the conference is using the results to support a package of bills to address voter access.

The major barriers that discouraged voters, according to the survey’s summary: the inability to vote early or to get an absentee ballot without an excuse; a lack of awareness of the dates of elections or the deadlines to register to vote; complicated laws about when to register for a primary; and limited voting hours.

These barriers tend to impact low-income workers, single-parent families, and caregivers the most, and in those groups, people of color, women, college students, and the elderly are disproportionately represented. If you’re a worker who’s been asked to stay late, or a single parent who can’t find childcare, you’re less likely to make it to the polling site. People who live in rural areas and those who don’t have easy access to transportation are also heavily affected.

New York State voters need to make voting rights a priority, says Iman Abid, director of the Genesee Valley Chapter of the New York Civil Liberties Union. “The fate of people’s civil liberties and civil rights are in the hands of their elected officials,” Abid says.

Rochester City Council Vice President Adam McFadden says he has done voting rights work in Alabama as a member of the National Black Caucus of Local Elected Officials and has seen how voter ID laws suppress the vote there. New York has a progressive advantage, he says, “but we have a lot of work to do around voter education and why it’s important for people to actually vote.”

Earlier this year, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order restoring the right to vote for New Yorkers on parole from prison. In April, McFadden organized a rally to encourage parolees to vote.

“I still deal with parolees who don’t know that there’s a law change,” McFadden says. “I had a 45-minute discussion, almost an argument, with a parolee trying to persuade him, even after showing him the actual law. You have to think: People have been taking shots at parolees for so long that they don’t know when they have legislation that’s supportive of them.”

Voting is about shaping policy and access to resources, says McFadden. As the US has expanded voting rights, there has always been an undercurrent of people wanting to attack and restrict that right in order to maintain control.

For people concerned about voting access, the question becomes how to “educate folks to understand what that attack is about and why it’s important for them to exercise their right,” says McFadden. “We have to do a better job of that.”

VOTER REGISTRATION

Voting rights advocates say that voter turnout increases when it’s easier and more convenient to participate in the process. And the process begins with voter registration.

Currently 17 states plus the District of Columbia offer same-day registration. New York, on the other hand, requires voters to register 25 days before an election, in person or by mail.

Twelve states and the District of Columbia have automatic voter registration. Oregon, which implemented automatic registration in January 2016, was the first state to do that, and it has seen increased racial, age, and income diversity in its voters.

Each state with automatic voter registration uses its own system, but the common practice is to automatically register people when they interact with a government agency unless they opt out.

If you live in Oregon, any time you interact with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles, a computer program automatically checks to see where you live, whether you’re old enough to vote, whether you’re a US citizen, and whether you’re already registered to vote. If you’re not registered and you’re eligible, the system sends that information to the Oregon Elections Division, which sends you a postcard telling you that you’ll be automatically registered to vote unaffiliated with a political party. If you want to enroll in a political party, you can note that on the post card and return it. Or, if you like, you can decline voter registration entirely, noting that on the postcard.

In addition to the states that already have automatic registration, another 20, including New York, introduced legislation for it in 2018. Democrats introduced a bill in the New York Senate that would allow registration to happen on the spot at certain government agencies, like the DMV, when applying for services from a municipal housing authority, or registering for classes at a state university. That bill is still in committee, and similar bills have been considered in the Assembly, but nothing yet has made it out of either chamber.

THE PRIMARY SYSTEM

While the turnout in general elections tends to be low, it’s even worse in primaries. Official numbers for last month’s 25th Congressional District Democratic primary haven’t been released yet, but Board of Elections officials estimate that voter turnout was 16 percent of registered Democrats in the district.

In 2017, the September mayoral primary drew out an estimated 25 percent, which is higher than the 23 percent turnout in the 2013 primary.

One reason for the low turnout in primaries is likely that federal and state primaries are held on different days. This year, for instance, the federal primary — locally, for the late Louise Slaughter’s Congressional seat — took place on June 26. State and local primaries will be on September 13, and the general election is November 6. During a presidential election year, as in 2016, adding a presidential primary means voters go to the polls four times during a year.

The primary process became a focus of the news during the 2016 presidential election, mainly because of the contentious fight between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. And the April 2016 New York primary, which Clinton won, highlighted additional problems with the state’s primary system.

New York has a “closed” primary system, which means you can vote only in the primary of the party in which you have enrolled. And if you have registered to vote but don’t want to be affiliated with a political party and didn’t enroll in one, you can’t vote in a primary. In a city like Rochester that heavily favors Democrats during the general election, the party primary takes on extra significance.

Compounding the primary problem is the state’s deadline to change parties. You can enroll in any political party when you register to vote — or you can register unaffiliated with any party. The deadline for enrolling in a party is the same as the registration deadline: 25 days before the next general election. Switching party enrollment is another matter, though, if you want to vote in a primary.

New York rules say this: “A change of enrollment received no later than 25 days before the general election shall be deposited in a sealed enrollment box and opened the first Tuesday following that general election and entered in the voter’s registration record.” In plain English: To change party enrollment, you have to plan months ahead.

Suppose, for instance, that in 2016, you had been enrolled as an unaffiliated voter. And as the Hillary and Bernie campaigns heated up, you decided you wanted to vote for Bernie Sanders in the April 19 Democratic presidential primary. Too late. You had to have changed your enrollment the previous fall: 25 days before the November 3, 2015, general election.

Sanders appealed to a lot of third-party and independent voters, says Mary Lupien, who was active in the local Sanders campaign, and he wasn’t getting his footing until a few months before the Democratic primary. “And so lots of people hadn’t heard of him in order to switch in time,” Lupien says.

EARLY VOTING

It seems intuitive that the longer the period in which people have to vote, the more likely they are to take advantage of it. Expanding polling site hours and enacting early voting, the NYCLU’s Iman Abid says, would give people more opportunity to participate.

And most states now permit people to vote days or weeks ahead of the formal election date. Studies have consistently shown, however, that early voting has little or no effect on turnout.

What does seem to increase turnout, though, is early voting combined with letting voters register right up to and including Election Day.

“Early voting doesn’t appear to help turnout by itself,” noted a December 2016 Washington Post article, “but it can be helpful to campaigns. If the campaigns take advantage.”

And here, too, New York is conservative. New York is one of only 13 states that don’t allow early voting. There have been attempts in the state legislature over the years to enact it, and in February, Governor Andrew Cuomo proposed funding for early voting starting in the 2019 general election. Funding for it was ultimately removed from the budget Cuomo signed, however.

Notably, studies have shown that early voting measures are especially used by the black community. In 2016, North Carolina’s Republican Party urged county election boards to reduce the number of early voting sites and hours. Some boards complied, and black early voter turnout in North Carolina fell 8.7 percent compared to 2012. Meanwhile, black early voting turnout grew in Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana.

ABSENTEE VOTING

In addition to limiting voting to a single day, New York State law requires you to vote in person, at your polling site, unless you have an absentee ballot. To get an absentee ballot, you have to fill out a form giving the reason you can’t vote in person, much as if you were in school and you had to get a doctor’s excuse for being absent.

And those reasons have to be one of the following: you’ll be out of your county of residence on election day; a temporary or permanent illness or disability will keep you from voting; you’re a primary caregiver; you’re a resident or patient at a Veterans Health Administration hospital; or you’re in jail awaiting a Grand Jury action or confined for an offense other than a felony.

“It’s just ridiculous that you have to say why you’re applying for an absentee ballot,” says the League of Women Voters’ Jennifer Wilson. “And it also makes it so that it’s easy to challenge those ballots in court.”

ACCURATE CLEAR INFORMATION

Low voter turnout can also be driven by a lack of information. Some registered voters don’t show up to the polls because they don’t know or forget when election day is or they don’t know enough about the candidates being voted on.

Making sure that accurate and clear information is sent out to voters would help boost participation, advocates say. While each New York county’s Board of Elections sends out basic information to voters, the extent of that information is often left up to that board’s discretion. For example, New York City’s Board of Elections creates a nonpartisan voter guide that contains general voting information, a list of candidates on the ballot, profiles submitted by those candidates, and information about city and state ballot proposals. That guide is released online, in video, and in print, which is mailed to every household with a registered voter.

That isn’t required by state law, and the Monroe County Board of Elections doesn’t send one. It does, however, send voters a letter with basic information on polling hours and voters’ designated polling place.

VOTER APATHY

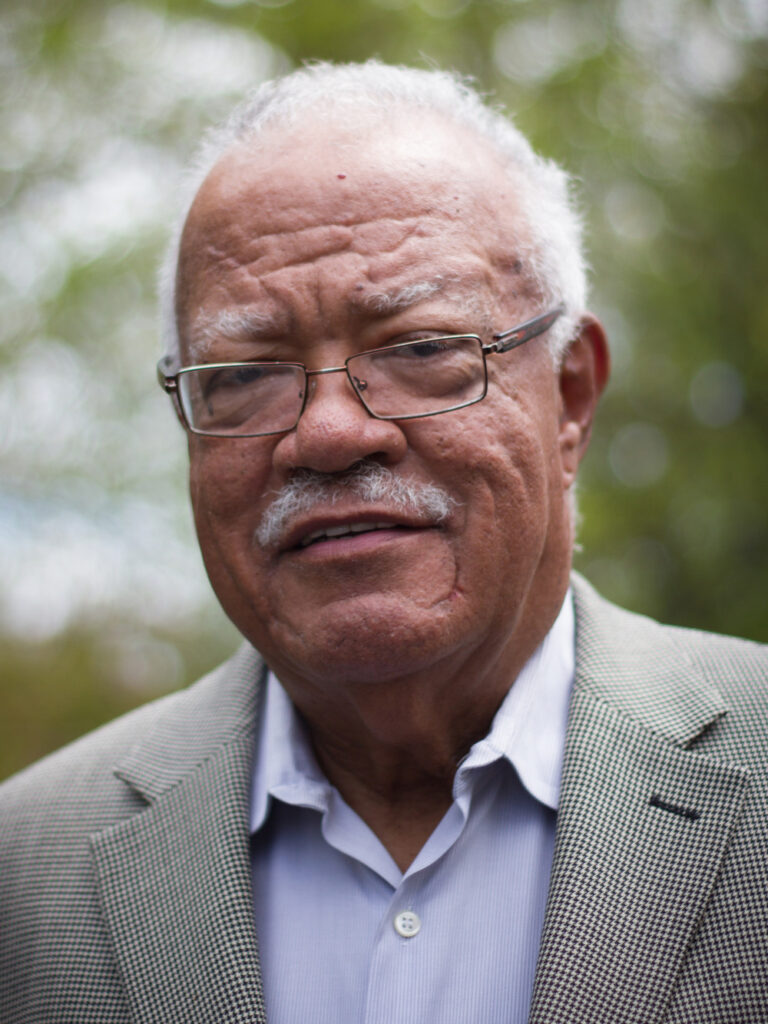

Former Rochester Mayor Bill Johnson believes low voter turnout is directly tied to voter apathy. People “are effectively turned off,” Johnson says. “They’re disenchanted with politicians, so they don’t see the need to vote.”

This isn’t a new issue, though, and it’s happening everywhere in the country. In the 1970’s, Johnson says, he conducted a city-wide voter registration campaign in Flint, Michigan, where he was living at the time. He encountered a lot of people who said “don’t bother me with that.”

“And that was in the year Richard Nixon was running for re-election,” Johnson says. “That was the year where a number of African-American candidates were running for local seats in Flint, in Genesee County. Even that did not inspire people.”

The burden is on the politicians, Johnson says. They have to show constituents that they’re working for their region.

“The politicians themselves, the elected officials, have to sincerely engage people, and not just at election time,” Johnson says. “When they are in office, they have to make themselves available, they have to listen, they have to be responsive. Just like anything else, when people see a benefit, they’ll participate.”

When politicians allow residents to be part of the solution, Johnson adds, and show that people that they’re listened to and even challenged, citizens will begin to work with those in power.

ADDING TO THE LIST

Also impacting voter turnout: purges of registration rolls. A recent study by New York University’s Brennan Center found that between 2014 and 2016, 16 million voters had been removed from registration rolls – some for legitimate reasons, but many not. And while many of the erroneous purges were in southern states, New York was not exempt.

New York’s attorney general found that more than 117,000 voters had been removed from voter rolls in Brooklyn. New York City Board of Elections officials said they were trying to remove voters who hadn’t voted or had no activity since 2008, and that they had begun removing people in late 2013 or early 2014. But that violates New York State law, and the board was required to review every voter registration removed from its lists beginning July 1, 2013.

Outdated voting machines, machines that are hard to use, long lines at polling locations: all of these deter people from voting. Negativity in campaign advertising or a particularly harsh race can sour voters. Gerrymandering can convince people that their vote doesn’t matter in a district heavily favoring one political party.

LOOKING AHEAD

The world has changed, Monroe County Elections Commissioner Tom Ferrarese says.

“You know, it isn’t like people work a shift at Kodak, and if they work a night shift they go and vote before, or if they work an early shift, they vote afterwards,” Ferrarese says. “People at factory gates campaigning, that was a big thing in the past. But that environment has changed.”

Families are busier today. There are more single-parent families, with adults who have to not only find time to vote but may also have to find childcare.

People are working longer hours and don’t fit into a traditional model. “All of that really plays into it,” Ferrarese says. “If we’re going to change those voting patterns, we have to look at various options.”

And locally, turnout has been growing in recent years, Ferrarese says. The November 2017 turnout was 3 percent higher than 2013, and 5 percent higher than 2009.

New York Senate Democrats made expanding voting rights their priority earlier this year with a package of bills addressing several issues: early voting; no-excuse absentee ballots; automatic voter registration; pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds; reforms in the rules on changing party enrollment; primary voting hours consistency; consolidation of federal and state primaries; advance notice of elections; and expanded language options for ballots.

It’s up to the governor and state legislature to pass progressive reforms, says Jennifer Wilson. When larger states like Texas, which implemented early voting decades ago, and California, which began automatic voter registration in 2016, are moving ahead of New York with reforms, it’s frustrating, Wilson says.

“At the end of the day,” Wilson says, part of the reason politicians “don’t want to pass it is they’re afraid that if they make voting easier, they’re going to get voted out of office.”

Jeremy Moule contributed reporting to this article. Find Open Mic Rochester at openmicroc.com.