Reflecting on Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” speech

[ COMMENTARY ] By Vanessa J. Cheeks

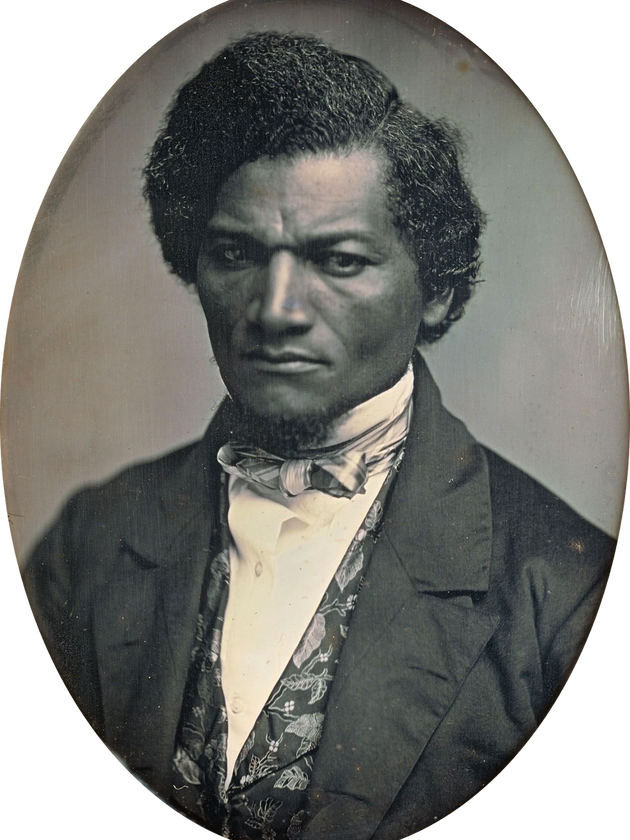

Frederick Douglass, on July 5, 1852, took to the stage at Rochester’s Corinthian Hall to deliver a speech to the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. He had been invited to commemorate the country’s 76th year of independence. He did praise the founding fathers for securing freedom for their new nation, but the celebrated orator, abolitionist, and former enslaved person used his speech to give a biting analysis of America’s hypocrisies in the thick of the anti-slavery movement.

Douglass’s speech, later titled “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” left no room for interpretation.

“The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common,” he said. “The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me.”

His words are as true now as they were then. Freedoms enjoyed by white Americans are not shared by black Americans, who are still fighting for equality.

This Independence Day is an opportunity to reflect on this important speech, available here. It’s also an opportunity to consider our current state.

Activist organizations like Black Lives Matter work to empower black people, but not without encountering a resistance that rivals the anti-abolitionist movements of Douglass’s time.

At the time they claimed enslavement of black people was an economic necessity; they believed our “naturally” brutish demeanor required a firm hand. And as slavery became illegal, those invested in our subjugation developed new ways to strip us of our dignity and freedom — mass criminalization being one of the more successful.

Last year, Steve Prator, sheriff of Louisiana’s Caddo Parish, lamented the passing of the state’s Justice Reinvestment Package. The package is expected to release 10 percent of the state’s non-violent prison population, a total prison population that was reported to be 66 percent black by 2010 census data.

“They’re releasing some good ones that we use every day to wash cars, to change oil in the cars, to cook in the kitchen, to do all that where we save money,” Prator said.

The “good ones” Prator mentioned make a measly $1 per hour washing those cars, if they’re lucky. That’s according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization that focuses on mass criminalization research. That same research shows minimum daily wages paid to incarcerated workers nationwide is now 86 cents, down from 93 cents in 2001. These slave wages can be garnished according to state policies. Prisoners, at times, end up owing the state in a system mirroring post-slavery sharecropping tactics.

This is modern day slavery and it is impacting blacks more than whites.

Blacks represent only 12 percent of the US adult population while whites make up 64 percent. In prison, though, black bodies occupy 33 percent of our prison system, edging out the white population by 3 percentage points, according to recent studies.

And how do we get there? We are at higher risk of being stopped by the police; we are incarcerated for longer periods of time for the same crimes; we are held without trial because we cannot afford bail and are kept in a cycle that makes it almost impossible for us to rehabilitate. It’s a cycle that lines the pockets of others.

“It is a fact, that whatever makes for the wealth or for the reputation of Americans and can be had cheap! will be found by Americans,” Douglass said in his speech.

Some Americans have found their wealth in the prison system. Following the war on drugs, private prisons promised cheap operating costs to keep up with the demand. In return, states promised a minimum number of prisoners to fill the beds. The Corrections Corporation of America was one of the first for-profit prison companies when it opened in 1983. In 2015, it recorded $1.9 billion in revenue.

This system couldn’t operate like this without public consent.

Recently, while watching an episode of “Cops,” a friend claimed the reason black people get shot by the police is because “they talk back.” As if talking back justified death.

The perception that black people are inherently loud, rude, or angry is often used against us. Our perceived uppityness also allows white people to distance themselves from what happens to us. We always have it coming.

If Trayvon Martin had simply let a stranger follow him home from the store, he might not have been shot. If Tamir Rice hadn’t been playing with a toy gun, in an open carry state, he might not have been shot. If Sandra Bland had not mouthed off, she may still be alive today.

When Colin Kaepernick kneeled during the national anthem to protest state-sanctioned violence against black people, that distance grew. Kaepernick’s actions were painted as unpatriotic despite his repeated attempts to clarify his issue was with the continued killing of black people at the hands of police. His small rebellion spread, and Kaepernick was fired.

The National Football League passed down a rule that all players must now stand on the field for the National Anthem or wait in the locker room.

But the United States was built on rebellion. “They felt themselves the victims of grievous wrongs,” Douglass said, “wholly incurable in their colonial capacity. With brave men there is always a remedy for oppression.”

The remedy he spoke of, and that you celebrate each year, came in the form of protests. They destroyed property and resisted government. It came in the form of a war. Today those same actions are vilified.

Black Americans fight a daily battle against systems that oppress us, people who hate us, and those that don’t believe our experiences as Americans differ from their own.

We also fight our allies who attempt to talk over us. Who take up space on the stage and, seeing the lack of black representation, do not move.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” Douglass asked. “I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Douglass found it abhorrent that a country could celebrate freedom from oppression while their slaves served the cake.

Like Frederick Douglass, I’m not sure I can celebrate freedom from oppression while it still persists. I am not enslaved in my country, not the way my family was. But I am not free in my own country — not the way white people are.

Our bondage comes in the form of systematic racism that is a remnant of the same American slave trade Douglass despised. It is small aggressions that wear us down. It is not shackles but it is oppressive and aims to silence those that would speak out. It’s also entire systems designed to ensnare us. It has killed black people to this day. It should not be celebrated. It won’t be by me.

Vanessa J. Cheeks is a writer for Open Mic Rochester. You can find her work at openmicroc.com.